|

|

Use the search box on the left to look for war crimes details, e.g. by trial location, location of alleged crime, type of crime, names of accused, names of victims, dates, etc

|

wo 235/830: MORI YOSHITADA (森義忠)

KAJANG, SELANGOR

4-6 MARCH 1946

|

ACCUSED

Chief Inspector Mori Yoshitada (森芳忠) CHARGE(S) Planned, prepared, ordered, participated in and/or failed to prevent or control arrest, confinement, torture and maltreatment, and the shooting and killing of a civilian. VICTIM(S) Lee Lim Chiang (died) Lee Ah Yin Lee Boon Lee Chen Foh Shen Chen Hoi Chin Akob (died) Raja Yahaya bin Raja Jema'at Mohammad Noor bin Rantan Jamaludin bin Haji Idris Hassan bin Sohat Yap Kon Lim DATE(S) OF CRIME(S) 10 March 1945, 15 April 1945, 1 August 1945 LOCATION(S) OF CRIME(S) Kajang, Selangor LOCATION OF TRIAL Kajang, Selangor TRIAL DATE(S) 4, 5, 6 March 1946 PRESIDENT Lt. Col. F.E. Figgures, Royal Artillery, Barrister-at-law* *Emergency Commission. Temporary Major 04/04/1943, Rank: Lieutenant, 2nd Rank: Captain (War Substantive) MEMBERS Maj. H.E.R. Smith, Royal Artillery* * Potentially H. Smith, Service number: 2586195, saw duty in Central Mediterranean and Italy, wounded on 10 Oct 1944, and attached to 166 Field Regiment, which was stationed in Malaya after the war Capt. J.M. Carter, Gurkha Rifles* * Likely J. Carter, Temporary Captain attached to General List regiment and War Office battalion, recipient of Imperial Service Order award |

PROSECUTING OFFICER

Major W.J. Davies, Royal Artillery DEFENDING OFFICER Capt. F. Whitgift, Royal Corps of Signals* * From Forces War Records - only one individual match, service number unavailable. Potentially ended service as 2nd Lieutenant (second rank: Lieutenant (War Substantive)). This unit was also involved in the Malaya Campaign after the war. WITNESS(ES) FOR DEFENCE Mori Yoshitada WITNESS(ES) FOR PROSECUTION Lee Ah Yin Chen Foh Shin Chin Fah Chen Hoi Chin Chang Siew Foo Ja 'Aman Haji Mah Foot Raja Yahaya bin Raja Jema'at Mohammad Noor bin Rantan Jamaludin Yap Kon Lim Syed Mohamed PLEA Not Guilty VERDICT Guilty SENTENCE Death by hanging Sentence carried out at 8am, 3 May 1946 at Pudu Gaol, Kuala Lumpur |

©IWM SE 6942

©IWM SE 6942

Mori Yoshitada was the officer in charge of the Kajang police district within Selangor state from 29 November 1944 until the end of the Japanese occupation. Prior to this, he was stationed in Singapore until 10 March 1944 and later transferred to Kuala Lumpur, followed by Kuala Kubu, before his final posting to Kajang. In the running of the police station, Mori was assisted by and delegated to Tagawa Hideo a.k.a. Chang Siew Foo – a Chinese sent from Formosa (Taiwan) which was then under Japanese rule (1895-1945) – and Heiho (auxiliary force) civilian subordinates, among them, in order of precedence, Inspector Yusoff and Penghulu Raja Yahaya.

Three charges were brought against Mori. The first involved the ill treatment and/torture of Chinese civilians who had been detained, imprisoned and subjected to torture, wherefore, one of them, Lee Lim Chiang died. The second charge involved the shooting of a Malay civilian, Akob, who had escaped from the police gaol along with seven or eight others but was recaptured. The third charge involved the arrest, confinement, torture and maltreatment of Raja Yahaya, Mohammad Noor and Yap Koon Lim.

Mori pleaded not guilty to the charges. In his defence, he claimed that only one prisoner had died while in custody from contracting dysentery. In the incident involving Akob, he claimed he was not present but involved in a raid in Kachau. He also denied arresting or ill-treating Raja Yahaya and Mohammad Noor, claiming that they had only been questioned. As for Yap Koon Lim, Mori pointed at Tagawa (a.k.a. Chang Siew Foo) as the source of the accusation that he had assisted three Chinese Heiho deserters, and that Tagawa’s allegations against him were due to ill will and vengeful motives.

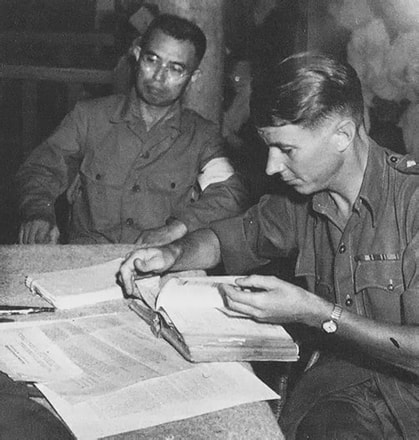

Image above: Mori Yoshitada with his British counsel. ©IWM SE 6942

Original caption: Counsel for the defence, Capt. F.Whitgift, Royal Signals, looks up a point during the trial.

Creator: Sgt. R. Park. Production date: 1946-03-05.

Three charges were brought against Mori. The first involved the ill treatment and/torture of Chinese civilians who had been detained, imprisoned and subjected to torture, wherefore, one of them, Lee Lim Chiang died. The second charge involved the shooting of a Malay civilian, Akob, who had escaped from the police gaol along with seven or eight others but was recaptured. The third charge involved the arrest, confinement, torture and maltreatment of Raja Yahaya, Mohammad Noor and Yap Koon Lim.

Mori pleaded not guilty to the charges. In his defence, he claimed that only one prisoner had died while in custody from contracting dysentery. In the incident involving Akob, he claimed he was not present but involved in a raid in Kachau. He also denied arresting or ill-treating Raja Yahaya and Mohammad Noor, claiming that they had only been questioned. As for Yap Koon Lim, Mori pointed at Tagawa (a.k.a. Chang Siew Foo) as the source of the accusation that he had assisted three Chinese Heiho deserters, and that Tagawa’s allegations against him were due to ill will and vengeful motives.

Image above: Mori Yoshitada with his British counsel. ©IWM SE 6942

Original caption: Counsel for the defence, Capt. F.Whitgift, Royal Signals, looks up a point during the trial.

Creator: Sgt. R. Park. Production date: 1946-03-05.

DOCUMENTS AVAILABLE ONLINE FROM INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT (ICC)

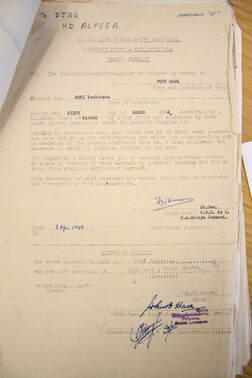

The record available online from ICC contains, quite unusually, the trial transcripts in its entirety. In fact, the TNA UK trial transcripts are incomplete in comparison, with the records stopping at page 109 (perhaps remaining pages were lost?). The ICC record, from page 110 onwards, includes a continuation of the cross-examination of Mori Yoshitada which was adjourned to the Kajang police station so that Yoshitada could describe the layout of the station, as well as questioning prosecution witnesses Chen Hoi Chin and Chan Siew Foo on-site. However, the TNA UK records contain some documents not included in the ICC record, e.g. Death Warrant (image right above).

Trial record: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/f130d2/

The record available online from ICC contains, quite unusually, the trial transcripts in its entirety. In fact, the TNA UK trial transcripts are incomplete in comparison, with the records stopping at page 109 (perhaps remaining pages were lost?). The ICC record, from page 110 onwards, includes a continuation of the cross-examination of Mori Yoshitada which was adjourned to the Kajang police station so that Yoshitada could describe the layout of the station, as well as questioning prosecution witnesses Chen Hoi Chin and Chan Siew Foo on-site. However, the TNA UK records contain some documents not included in the ICC record, e.g. Death Warrant (image right above).

Trial record: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/f130d2/