ABNORMAL TIMES: BEYOND THE SOOK CHING MASSACRES

For the average civilian, the Japanese occupation represented “abnormal times.” Abnormal, according to prosecutor S.K. Bannerji, because those in authority “exercised an absolute discretion over the lives and property of the civilian residents and more often than not, this discretion was exercised to the fullest possible extent and in the most arbitrary manner.”[1] The sense of abnormality was magnified by the actions of the kempeitai military police who had unlimited powers to arrest, torture and mete out summary judgement. Whether the purported infringements were valid or speculative, no one was above suspicion. Outside the physical threat to life and limb, and perhaps even more dire, was the threat of being randomly targeted.

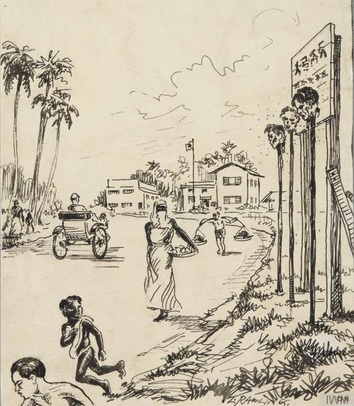

[Left: The severed heads of three Chinese men placed on the end of tall wooden poles on the side of a road. © Leo Rawlings' estate. IWM Catalogue No. Art. IWM ART LD6042. Leo Rawlings was a POW captured in Singapore. For more info about Rawlings, click here.]

In some incidents, the candidates for arrest were predictable, as in SSVF personnel T.W. Ong’s case. During the shukusei (cleansing) operations of February 1942, Ong was arrested and subjected to 21 days of torture before he was set free. Though he was released, this did not guarantee against future persecution. Two months later, Ong was detained and subjected to 27 days of torture; and again in September 1943 for 24 days.[2] It seemed that once a suspect, one likely remained blacklisted. Sometimes, this led to tragic results as in the case of Low Yoon Kim. In May 1945, Low was summoned by Sergeant Sasaki Saburo to the Telok Anson police station. A Chinese informant was sent to fetch him. When he returned home three hours later, Low had clearly been tortured; his body was covered in burns from electric shocks. Two weeks later, he was again summoned to meet Sasaki in a nearby park. This time, Low did not return; his son testified to seeing his body floating in the river.[3] However, it was never established in court as to why Low was detained twice; it seemed he had simply become a suspect.

Ong and Low’s stories are representative of the numerous incidents of torture documented within the war crimes cases. A collective reading yields an overwhelming sense of random suddenness. Koh Soo Keng for example was arrested on 14 August 1944 while at the park and later subjected to four months detention and torture. Of his ordeal he said, “I was not told the reason, but I was asked to admit and I did not know what to admit.”[4] Like Koh, many victims were baffled as to why they were persecuted; few admitted to acts of resistance or heroics. One would imagine that it would have been advantageous for victims to admit they had been involved in anti-Japanese activities or had harboured pro-British attitudes. Instead most exhibited hapless ignorance. Lim Guet Keow for instance was arrested at her home in November 1942 and tortured in a cell adjoining her husband’s. Her husband died after two months of incarceration. When asked why they had been arrested, she answered simply, “I was not told for what reason.” When pressed as to whether her husband had been involved in any subversive activities, she was adamant, “No Sir, my husband didn't join any [secret] society.” What about her, had she been involved? “No, Sir. Never mixed up with any friends,” she claimed, “always in the home.”[5] Similarly, Yu Song Moi recalled how, along with 26 others, she had been arrested in January 1945. After months of torture, she was admitted to Sibu Hospital. When asked if she knew why she had been arrested, she replied, “As far as I know, no reason at all.”[6]

Kempeitai procedure, it seems, involved casting the net of aspersion far and wide, often abetted by baseless accusations from local informants, only to whittle down the throngs of guileless suspects through a systematic escalation of abuse. The prized objective was intelligence, be it admission of wrongdoing or providing potential leads on subversive activities. When coercion and abuse failed to produce a confession, attempts often turned towards cultivating the victim as a future informant, thus perpetuating the cycle of (mis)information. Lam Keong Kong for instance was arrested with his father, mother, uncles, brother and sister-in-law. He was suspected of hiding firearms for the resistance. After six months of torture, when the Japanese were satisfied that there was nothing to be elicited from Lam, he was released. During this time, two of his family members died in custody while the rest went missing. According to Lam, he had been released on condition that he report back periodically to provide information on suspected communists. The accused however provided conflicting testimonies on Lam’s involvement with the kempeitai: one claimed that Lam had become friendly with his previous torturers on his own accord, even inviting them home to dinner and lending 200 yen to another; another attested that Lam had served as an orderly to the station’s staff sergeant while in detention, which was unusual for prisoners; and yet another denied Lam was ever an informant or under kempeitai employ.[7] Lam stated that he was “forced to have a friendship” with the kempeitai and admitted he had received “favourable treatment” after his release, including gifts of rice.[8]

Kempeitai officers were under immense pressure to produce intelligence, no matter how dubious the methods employed or the information obtained. Sergeant Shin Shigetoshi testified that his commander had demanded “information and results at all costs;” failure to do so, he claimed, was tantamount to insubordination which was a punishable offence.[9] Similarly, Lim Say Chong, a Chinese clerk at the Ipoh kempeitai office, overheard the officer-in-charge Anraku Chosaku order two Taiwanese interpreters to extract information from a prisoner. Anraku allegedly told the men: “Take him away, must get a confession out of him even if you have to kill him.”[10] The suspect, Foong Koon Hoy, subsequently died as a result of water treatment.

Victims often caved in and confessed to crimes they knew little about. Some even went to extreme measures to satisfy their torturers. Lam Nai Fook affixed his thumbprint to three statements he was given, even though he admitted: “I was made to sign but what were the contents I do not know.”[11] Tan Cheng Chuan was similarly perplexed. The Japanese had accused him of being involved with the resistance. After days of torture, a Chinese detective, Chia Koon On, urged him aside to confess lest he be beaten to death. Whether Chia had Tan’s interest at heart is unknown but Tan eventually confessed that he was a communist. “Then the Japanese gave me a cigarette,” he recalled. “They asked me to which communist I belonged to so I answered the Triangle Communist. In fact I don't know what Triangle was, I bluffed them.”[12]

While torture was endemic, several accused steadfastly denied that kempeitai policy advocated abuse.[13] Others offered conflicting testimonies.[14] Among them, Sergeant Major Otoda Hiroshi’s deposition stands out as he was the only individual, among a total of 162 accused, who pled guilty to the charges levied against him. Otoda however justified his plea; he had merely discharged his duties according to “the policy of the kempeitai and living up to its traditions to the best of my ability” and he sincerely believed that his “treatment of [the victims] was for the common good.”[15] During cross examination, he described plainly the interrogation methods practised at the Alor Setar police station. These were summarised during the prosecution’s closing address:

…beating and poking with sticks, kicking, slapping the face with hands or slippers, suspending upside down, suspending by the wrists tied behind the back, burning with hot strips of metal or cigarette ends, water torture – victim placed on his back, flannel over his face, water is played from a hose attached to a tap, and water is sucked in, this continues until the victim’s stomach is filled with water and distended, sometimes a plank is placed upon the stomach and pressed or stood upon until the water is forcibly expelled.[16]

The methods employed at Alor Setar were common practise.[17] Clearly, these abusive techniques were either well established and therefore sanctioned, or widely shared and therefore encouraged. Euphemisms were often used to describe various torture methods, as in ‘water treatment’ or ‘electric treatment.’ They differed only slightly from field office to field office; ‘water treatment’ for example could mean dunking the victim’s head into a basin of water,[18] placing the victim’s head face upwards under a flowing tap,[19] submerging the victim upside down inside a tank filled with water[20] or lowering the victim into a well.[21] However, at times, rather bizarre methods were also employed. In Penang, torturers often flung the station’s pet monkey at suspects during interrogations.[22] In Kota Bahru, Ho Chid’s fingernails were extracted; he was then wrapped in barbed wire and rolled about on the floor.[23]

Abuse was steadily escalated when a suspect proved uncooperative. Lim Nai Meng’s story is a prime example. He was arrested on suspicion of having organised an anti-Japanese unit. After repeated beatings over several days which rendered him semi-conscious, he was suspended from the ceiling with ropes tied to his thumbs until “the bones inside it could almost be seen.”[24] Burning papers were applied to his buttocks, legs and private parts. Intermittently, between beatings, he was submerged in a water tank. When returned to his cell, his hands were bound for fear that he would commit suicide. Nevertheless, Lim was found one morning with his tongue bitten off. He had expired without divulging a single piece of useful information.

For those who withstood torture their ordeal did not stop as long as they remained in captivity. Ultimate survival depended on their capacity for endurance, as rations were scarce, medical attention inadequate and detention cells vermin-infested. Some prisoners proved resilient, such as Low Kiang Pin, who endured 10 months of torture until liberation on 6 September 1945.[25] Many were less hardy, succumbing to a combination of torture, illness and deprivation. How many endured captivity is inconclusive as Japanese record-keeping was erratic, highly inaccurate and most records were destroyed.

The situation at Penang Prison is illustrative. Available records admitted into evidence reveal large gaps, most notably between March 1942 and March 1944, when registrations of death were suspended.[26] It was estimated however that the death toll throughout 1943 averaged 10 to 15 a day.[27] Available records dating between 22 March 1944 and 24 August 1945 indicate that 589 persons met their demise. Of these recorded deaths, 15 were ascribed to hanging while the rest were attributed to illnesses, from beriberi, tuberculosis, septicaemia to even senility.[28] Whether these deaths were hastened by complications arising from torture is unknown. Evidence suggests medical officers were often instructed to downplay prisoners’ health conditions or falsify the causes of death.[29] Hence, deaths attributed to illness belie potential ill treatment. When Lee Teck Hua retrieved the body of his son at Outram Road Jail, he was convinced that Lee Tee Tee had been “beaten to death” for he was “beaten until unrecognisable.”[30] He had to rely on a clerk to point out the body. The death certificate however stated the cause of death simply as beriberi.[31] This suggests that even when documentation exists, it may present only a partial picture of reality. As further proof, it should be noted that records of the 15 Chinese who were allegedly hung in Penang Prison span only three months, from June to September 1944.[32] It is dubious there were no other hangings before or after this period. Similarly, between 22 September 1942 and 10 August 1943, only two Indians, three Malays and 13 Chinese were reportedly executed.[33]

According to Corporal Bhag Singh, the Indian head of security at the prison, there were at least 1,500 prisoners in 1942 alone. While 500 were released, many died from starvation. By April 1943, Singh testified that the “120 that were left were just about to die.”[34] Corroborating testimonies from Malay and Indian sub-warders suggest that the prison population remained substantial throughout the occupation. There were three primary halls with multiple cells. Each cell held between 15 and 20 prisoners. Hall A and B were reserved for Chinese prisoners, while Hall C, which had 104 cells, had a mixed population of Chinese and Indian inmates, among them up to 800 women.[35] The women were subjected to similar ill treatment as the men. Indian medical officer Govindasamy recalled seeing female corpses in the hospital mortuary, where “the women were very thin, emaciated and their legs swollen up.”[36] Cecilia Wong, a Chinese matron attached to the women’s ward at Penang Hospital, recalled attending to Wong Kah Foong in October 1943 and Hwa Lan in February 1944.[37] Both had been tortured; one woman alleged she had been stripped, tied up and her genitalia prodded with a stick. In Kajang prison, Chen Foh Shin testified that during his incarceration, he knew of one cell that housed only women inmates.[38] At the Ipoh kempeitai office, Leong Sie Chun recounted how a female prisoner of 20 had been stripped naked during an interrogation, her breasts pierced with wires and her genitalia scorched.[39]

The only available records on deaths at Penang Prison list the 589 victims by name. Apart from these identified prisoners, it is impossible to know for certain who or how many were incarcerated, let alone how many were lost. Corpses were disposed of at multiple mass burial sites. Chinese caretaker Goh Teng Leong was among several employed to remove bodies from the prison and bury them at Rifle Range near Kampung Bahru. He testified that on average, he buried between three and six bodies a day. When asked what was the most he ever buried in a day, he replied, “five, six, seven or eight, I am not certain.”[40]

Another mass burial site was Bukit Dunbar on Thien Eok Estate. When this site was discovered by the War Crimes Investigation Unit No. 6, a partial excavation was undertaken. One mass grave measuring 50 feet in length and three feet wide was opened up to a depth of six feet, even though it was estimated that the grave was possibly 10 feet deep or more. Major Douglas Hayhurst counted 232 skulls, after which the remains were reinterred in situ. He also testified that there were at least three mass graves on the site but these were not disturbed.[41] Even though the prison population was not exclusively Chinese, it appears that the authorities assumed that since the majority of victims were Chinese, there was no need to consult anyone but local Chinese associations about this discovery. Furthermore, the value of the site as visual and physical testament of Japanese atrocities was not lost on the administration. Photos of the exhumations were provided to the Chinese press even as the trial was underway.

Persecution by the kempeitai was not restricted to suspects. Often, family members were also abused to compel the suspect to talk. Dr. Sybil Kathigasu, of Eurasian ethnicity, endured needles stuck under her fingernails and canes pressed into the sockets of her kneecaps. She was also burned with heated iron rods and hung upside down and beaten. Yet she refused to admit she had provided medical assistance to guerrillas. The kempeitai changed tack; they strung up her 7-year-old daughter in a tree and lit a fire beneath her. Kathigasu stood firm; she knew that if she spoke it would mean “death for thousands of people up in the hills.”[42] Unable to break her, the kempeitai released her daughter but turned their attention to her husband. Under torture, he broke down and Kathigasu was sentenced to life imprisonment. In another incident, Tham Keng Yam’s father was escorted to his residence and subjected to water treatment in front of him, after Tham denied owning a radio set. They were both beaten and incarcerated. Tham was asked to identify his father’s body and released. Tham was simply told, “Your father’s case is over and you are free now.”[43] Like so many others, Tham had no recourse; it was just the way things were.

The picture of the occupation that emerges from the trial cases is one of a deep and hopeless malaise. Many appear to have succumbed to apathetic helplessness or bewildered disconcertment. When violence occurred in their midst, they were reduced to meek onlookers. When violence was visited upon them, there was hapless resignation. Never was this more evident than in cases involving random and sudden violence. The plight of Anis bin Elok is a prime example. A stranger to Sibu, the Malay man had wandered into the town. As he was passing the police station, he heard the cries of a man being tortured and entered the premises to enquire. For his curiosity, he was strung up and beaten and his torturers left him tethered to the ceiling. When they returned an hour later, he had expired. Anis’ body was cut into pieces and thrown into a nearby river.[44] In Rengan, Chong Chuan’s husband was rounding up their drove of pigs for the night. Without warning, a report rang out in the dark. Her husband, Hee Than, was killed by Hayashi Sadahiko with a single rifle shot from 20 feet away. Chong was cautioned to not report the incident on pain of death.[45] In Melaka, Tay Kiam Aik was arrested and brought to the police station. The Chinese man appeared to be of unsound mind; when questioned, all he did was laugh. Tay was promptly beheaded, his head placed in a wooden box and displayed at a road junction.[46] In Perak, Tan Lim’s son was bundled into a car by several Japanese officers. He followed on his bicycle and saw his son taken into a shop. Several hours later, Tan Put Kim was escorted to the back of the premises next to a river. Tan Lim then heard the sound of gunshots and watched his son’s body float away.[47] In Bentong, Tan Ching Leong was escorted between a Japanese officer, Shima Nobuo, and a local interpreter. The party marched up Ah Peng Street, where they met with another Japanese officer named Wada. The district officer was a Malay man known as Dato’ Hussein, who had been in a meeting with Wada. He testified that the officers exchanged a few words, following which, Shima “unsheathed his sword and executed the Chinese with one stroke.”[48] The beheading was perfunctory and accomplished with aplomb. It was witnessed by local residents, who kept their heads down and went about their business.[49] Tan’s corpse was left in the street until midday.[50]

The Japanese army displayed similar equanimity in the commission of wholesale slaughter. In Negeri Sembilan, officers of the 11th Regiment of the 25th Army were instructed to “summarily execute any Chinese found in their areas.”[51] On 10 March 1942, a force of 70 soldiers arrived into Senaling. They arrested four prominent Chinese families and an indeterminate number of Chinese. The men, women and children were taken to Kuala Pilah by lorry. Behind the town’s former English school, they were bayoneted and cut with swords. Four days later, the regiment returned to Senaling where Captain Iwata Mitsugi briefed the assembled villagers. He announced that the four families would not be returning. Their belongings were given to a Malay villager to auction. On their way out of the village, the regiment rounded up 76 Chinese refugees who had been squatting in the market and marched them to Kuala Pilah. Once there, some were released while the majority met the same fate as the previous victims. The following day, the same regiment marched into the nearby town of Parit Tinggi and assembled the villagers under the ruse of dispensing safe passes. The 675 men, women and children were despatched in the surrounding vicinity and the village was set alight.

Sporadic lightning raids on homes, villages and businesses were recorded throughout the occupation.[52] These operations were intended to weed out anti-Japanese guerrillas, turn up outlawed items or punish anyone suspected of providing support to the resistance. In an unusual case, the Chinese village of Sungei Lui was raided in August 1942 purportedly to search for a missing Malay man named Zakanah bin Bassir.[53] The significance of Zakanah was not established in court. The men were shot in batches of 10, while the women and children herded into a shop where they were machine-gunned. In Tenghilan, during a raid on Chau Kee Sundry Shop in October 1943, the proprietor was found in possession of a Nationalist Chinese flag and summarily executed.[54] A search for “Chinese agitators” on Mentanani island in February 1944 led to the mass killing of 60 Suluk men, women and children, and several Chinese.[55]

Sometimes, the objective of the lightning raids was unclear. In the village of Kuala Kubu for example the villagers were preparing for a wedding on 28 April 1944 when a contingent of soldiers arrived and fired a shot into the air. The villagers fled helter-skelter. Seven Chinese men were herded into a house, bayoneted and the house was set on fire.[56] When asked why the villagers had been targetted for Japanese action, Lei Kow, one of the surviving victims, replied, “I do not know the cause.” When asked by the defence counsel if he had been “in league with the notorious Chinese bandit Communist Party?,” Lei Kow denied this. “No, not so,” he answered, “I devoted all my time to planting food crops. I have a lot of children.”[57] The defence counsel’s attempt to paint the victims as anti-Japanese was unsuccessful. Similarly, in December 1944, a 30 man-strong detachment comprising Japanese officers and Indian, Malay and Chinese sub-police, raided the Soon Foh mine in Kampar. The coolies were asked if there were any anti-Japanese people on site.[58] When no one stepped forward, the coolies were beaten, and the staff quarters and machinery set on fire. Why did the Japanese scupper production at the mine? It is highly unlikely that their aim had been to disrupt output. There appeared to have been little tangible benefit to such operations except to keep the populace on edge.

In 1945, as the tide of war began turning against the Japanese, there was a corresponding escalation in atrocities. The highly-charged atmosphere bordered on paranoia; any whiff of dissent or suspected infraction was met with swift reprisals. Civilians careless enough to let slip that a future Allied victory was imminent were accused of spreading propaganda and summarily disposed of.[59] Repressive measures were stepped up to tighten security and maintain control. In Kampar town for example 40 to 45 “beggars” – most likely displaced persons or refugees – were trucked to the outskirts in early 1945 and shot; in May, several Chinese teens suspected of theft were executed without trial; in June, Chinese farmers who were clearing jungle foliage without obtaining prior permission were machine-gunned on site; that same month, a Malay man, Ali Zaman, was executed for “blasphemy” against the emperor; and in August, six pork sellers and several others were rounded up in the town market for “spreading communist propaganda” and shot.[60]

From mid-1945 onwards, there were concerted efforts at eliminating witnesses and destroying evidence. Captain Harada Kensei testified that in preparation for imminent Allied landings, the Jesselton kempeitai had received the order to implement the “Third War Plan.” This, he said, involved “clearing out all elements detrimental to the peace,” including blacklisted persons and suspects in custody.[61] The existence of a ‘Third War Plan’ has not been raised in any known academic discourse on the Japanese occupation nor did any other accused mention it. Nevertheless, it is clear that ‘clearing out’ activities accelerated during this time. In Keningau, prominent civilian internees were marched to Renau and executed by firing squad in July 1945. They included the British Chief Secretary, Silis Drummond Le Gross Clerk, rubber plantation owner Ronald Macdonald, American engineer Henry William Webber, Dr. Valentine Alexander Stookes and the Chinese Consul-General, Cho Huan Lai.[62] That same month, 17 Chinese internees at Bentong police station were trucked to the 11th mile Karak Road and killed.[63]

Elimination operations continued even after the Japanese surrender on 15 August. Between late August and early September 1945, the cells at Kampar police station were emptied out. Malay constables testified that the Chinese prisoners were shot in batches in the neighbouring hills.[64] On 5 September in Melaka, 14 Chinese civilians were arrested from among 50 who had gathered at the Overseas Chinese Association building. They were spirited away to a remote island where they were bayoneted and thrown down a well.[65] Having heard of the Japanese surrender, they had gathered to discuss future plans for the community. While the atrocities described in some detail above are not exhaustive, these multiple accounts, it is hoped, convey in some limited measure the destitution and degradation unleashed during the occupation. Wives were left to dig for the bones of their husbands on the beach;[66] fathers fished their sons’ bodies out of rivers;[67] while strangers disposed the corpses of unknown dead.[68] Meanwhile, profiteers flourished in the black market, women canoodled with Japanese officers at dance halls, desperate mothers scavenged for food, and scores of orphaned feral children roamed the streets, even as informants exchanged accusations for favours.

Such abnormal times were made possible by the undercurrent of chronic terror which ran beneath the surface of normal living. In maintaining a violent hegemony, the Japanese administration was aided by local Chinese, Malay, Indian and Eurasian auxiliary policemen, translators, jailers, mortuary hands, doctors, sub-wardens – and the list is large for those who made up the cogs of the occupation machinery – who, while often reluctant, were obsequious servants. Many felt fear and in turn perpetuated fear. The participation of collaborators, as the historian Timothy Brook has pointed out, allows for the narrative of atrocity in war to be normalised.[69] Those in Japanese employ inadvertently legitimised and maintained the Japanese system of terror.

[1] Prosecutor’s Closing Address, WO235/877: Trial of Anraku Chosaku, Kampar, 20-21 June 1946, TNA.

[2] WO235/872: Trial of Sgt. Maj. Toyoda Akiichi, Singapore, 3-8 July 1946, TNA.

[3] Testimony of Low Thiong Mong, WO235/866: Trial of Sgt. Sasaki Saburo, Telok Anson, 17-18 June 1946, TNA.

[4] Testimony of Koh Soo Keng, WO235/819, TNA.

[5] Testimony of Lim Guet Keow, WO235/819, TNA.

[6] Testimony of Yu Song Moi, WO235/890: Trial of Lt. Murakami Seisaku and three others, Singapore, 14-17 August 1946, TNA.

[7] Testimonies of Hase Ryosuke, Murata Yoshitara and Shin Shigetoshi, WO235/819, TNA.

[8] Testimony of Lam Keong Kong, WO235/819, TNA.

[9] Testimony of Shin Shigetoshi, WO235/819, TNA.

[10] Testimony of Lim Say Chong, WO235/877, TNA.

[11] Testimony of Lam Nai Fook, WO235/819, TNA.

[12] Testimony of Tan Cheng Chuan, WO235/872, TNA.

[13] See for example testimonies from: Maj. Onishi Satoru, Sgt. Uekihara Susumu and Sgt. Matsumoto Mitsugi, all three were based at the kempeitai headquarters in Oxley Rise, Singapore; WO235/843, TNA.

[14] In the same trial as above, i.e. WO235/843, other accused provided convoluted testimony as to what methods were employed. Most agreed that physical abuse was used but either denied engaging in such acts themselves, or that abuse was perpetrated only when interrogators had run out of options. See testimonies from: Sgt. Matsumoto Mitsugi and Sgt. Shimomura Tomohei.

[15] Appendix ‘E’: Petition against the Sentence of a Military Court, 11 February 1946, WO235/815, TNA.

[16] Prosecuting officer’s closing address, WO235/815, TNA.

[17] For example, Sgt. Nishi Yoshinobu, who was based in the Kuala Lumpur kempeitai office, describes similar torture methods. See: Evidence ‘A’: Summary of Examination, 24 June 1946, WO235/870, TNA.

[18] Testimony of Tham Keng Yam, WO235/821: War Crimes Trial of Sugimoto Heikichi and two others, Singapore, 5-7 February 1946, TNA.

[19] Testimony of Low Kiang Pin, WO235/819, TNA.

[20] Testimony of Sithamparam Pillay Karthigesu, WO235/953: Trial of Ogata Tsuyoshi, Kota Bahru, 21-24 October 1946, TNA.

[21] Testimony of Bhag Singh, WO235/931, TNA.

[22] Testimony of Syed Mohd, WO235/931, TNA.

[23] Testimony of Sithamparam Pillay Karthigesu, WO235/953, TNA.

[24] Testimony of Chong Seng Ee, WO235/872, TNA.

[25] Testimony of Low Kiang Pin, WO235/819, TNA.

[26] Testimony of Sheikh Ahmad Jelani, WO235/931, TNA. Sheikh Ahmad Jelani was the deputy registrar of births and deaths at the prison hospital. His testimony is corroborated by Corporal Bhag Singh who claimed that deaths in the prison were not recorded in 1942 and 1943, but that record-keeping resumed in 1944.

[27] Testimonies of Dr. Randmangan Letchmanasamy and Abbas Hussein bin Bacha, WO235/931, TNA.

[28] Evidence ‘J:’ List of Deaths in Prisons (Penang) Registered at General Hospital Penang, WO235/931, TNA.

[29] See for example: Testimony of Ayadurai, WO235/843, NA. Ayadurai, a senior dresser at Outram Road Prison hospital was tasked with recording admissions; he testified that “Mikizawa, the Japanese Commandant, was always objecting to persons being stated to be other than in good condition” even though “with very rare exceptions, no prisoner was ever in good condition.” The death of Ngu San Tieh was recorded as due to natural causes even though he died while being tortured; see: Testimony of Victor Francis Xavier, WO235/878: Trial of Sase Yoriyuki, Singapore, 17-19 July 1946, TNA. The death of Lall Singh Bull was recorded as an accident, though he too died while being interrogated; see: Testimony of Gorbex Singh, WO235/870, TNA.

[30] Testimony of Lee Teck Hua, WO235/843, TNA.

[31] Testimonies of Lee Keok Seng, WO235/843, TNA.

[32] Evidence ‘H:’ Return of Deaths in the Penang Prison from 1.1.1944 - 3.9.1945 (Jud: Hanging), WO235/931, TNA.

[33] Evidence ‘G:’ Deaths (Executions) from 1.6.42 – 14.2.44, WO235/931, TNA.

[34] Testimony of Bhag Singh, WO235/931, TNA. On the prison population and conditions, see also corroborating testimonies from sub-warders Kassim Ali bin Hashim, Ismail bin Mat Taib, Hashim bin Arshad and Abbas Hussein bin Bacha.

[35] Testimonies of Hashim bin Arshad and Hashim bin Kaji Kadar, WO235/931, TNA.

[36] Testimony of Govindasamy, WO235/931, TNA.

[37] Testimony of Cecilia Wong, WO235/931, TNA.

[38] Testimony of Chen Foh Shin, WO235/830, TNA.

[39] Testimony of Leong Sie Chun, WO235/837, TNA.

[40] Testimony of Goh Teng Leong, WO235/931, TNA.

[41] Testimony of Douglas Hayhurst, WO235/931, TNA.

[42] Evidence ‘C’: Affidavit of Sybil Kathigasu, WO235/837: Trial of Sgt. Yoshimura Ekio, Ipoh, 18-20 February 1946, TNA. Upon liberation, Kathigasu was sent to London for medical treatment. She was awarded the George Medal in 1947. However, before she could return home, she succumbed to septicaemia and died. Her story is documented in her memoir, No Dram of Mercy.

[43] Testimony of Tham Keng Yam, WO235/821, TNA.

[44] Testimony of Jackie Young, WO235/878, TNA.

[45] Testimony of Chong Chuan, WO311/543, Case No. 65225: Trial of Sgt. Hayashi Sadahiko and Toriumi Mamoru, Johore Bahru, 2-12 July 1947, TNA.

[46] Testimony of Ali bin Sidan Idin, WO235/888: Trial of WO Osaki Giichi and two others, Melaka, 26-27 August 1946, TNA.

[47] Testimony of Tan Lim, WO235/866, TNA.

[48] Testimony of Dato Hussein, WO235/881: Trial of Sgt. Maj. Shima Nobuo, Bentong, 15 July 1946, TNA.

[49] Testimonies of Ho Swee Kei, Wong Chun, Chia Ah Fah and Ng Hai Chew, WO235/881, TNA.

[50] Testimony of Tan Cheow, WO235/881, TNA.

[51] Abstract of Evidence, WO311/543, Case No. 65272: Trial of Capt. Watanabe Tsunahiko and two others, Kuala Lumpur, 22 Sept ember-13 October 1947, TNA.

[52] For other raids, see: Swee Radio Service, a shop in Bukit Bintang Road in Kuala Lumpur, in November 1943, WO235/904, TNA; Khoo residence, Singapore, in October 1943, WO235/907: Trial of Sgt Okayama Hikoji, Singapore, 25-26 June 1946; multiple raids on Pinji Estate including July 1945, WO235/845: Trial of Nagayasu Mamoru, Ipoh, 1-2 May 1946, TNA; Bukit Koman in May 1944, WO235/873: Trial of Sgt. Maj. Tanaka Hideo, Raub, 18 July 1946, TNA; Raid on Cho residence, Brinchang, in June 1945, WO235/866, TNA.

[53] WO311-543, Case No. 65275: Trial of 2nd Lt. Hashimoto Tadashi , Kuala Lumpur, 21-29 July 1947, TNA.

[54] WO235/926: Trial of Kato Chuichiro, Borneo, 20-22 November 1946, TNA.

[55] WO235/882: Trial of 2nd Lieut. Shimizu Kiyogi and seven others, Singapore, 15-29 July 1946, TNA.

[56] WO235/824, TNA, 14.

[57] WO235/824, PRO, 14.

[58] Testimonies of Yeong Choy and Cheong Hon Leong, WO235/877, TNA.

[59] Such incidents were recorded in Penampang, Telipong, Menggatal, Kuala Belait and Jesselton between June and July 1945; see: WO235/884: Trial of Capt. Harada Kensei, Singapore, 8-11 July 1946, NA, and WO235/833, TNA.

[60] Testimonies of Lall Singh, Soo Peng Hui, Tan Teck Oi, Niaz Mohamed and Seah Chong Sin, WO235/877, TNA.

[61] Testimony of Capt. Harada Kensei, WO235/928, TNA.

[62] WO235/883: Trial of Lt. Col. Abe Kiichi and three others, Labuan, 29 April-4 May July 1946, TNA.

[63] WO235/880, TNA.

[64] WO235/877, TNA.

[65] WO235/875: Trial of Capt. Kamezawa Matsutoshi and ten others, Melaka, 5-6 July 1946, TNA.

[66] Testimonies of Edith Chong and Mrs Leong Chong Fah, WO235/833, TNA.

[67] Testimonies of Tan Lim, Low Thiong Mong and Beh Chin, WO235/866, TNA.

[68] Testimonies of Tham Heng, WO235/880, NA; and Lee Ah Fong, WO235/926, TNA.

[69] Timothy Brook, Collaboration: Japanese Agents and Local Elites in Wartime China (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007), 242.

[Left: The severed heads of three Chinese men placed on the end of tall wooden poles on the side of a road. © Leo Rawlings' estate. IWM Catalogue No. Art. IWM ART LD6042. Leo Rawlings was a POW captured in Singapore. For more info about Rawlings, click here.]

In some incidents, the candidates for arrest were predictable, as in SSVF personnel T.W. Ong’s case. During the shukusei (cleansing) operations of February 1942, Ong was arrested and subjected to 21 days of torture before he was set free. Though he was released, this did not guarantee against future persecution. Two months later, Ong was detained and subjected to 27 days of torture; and again in September 1943 for 24 days.[2] It seemed that once a suspect, one likely remained blacklisted. Sometimes, this led to tragic results as in the case of Low Yoon Kim. In May 1945, Low was summoned by Sergeant Sasaki Saburo to the Telok Anson police station. A Chinese informant was sent to fetch him. When he returned home three hours later, Low had clearly been tortured; his body was covered in burns from electric shocks. Two weeks later, he was again summoned to meet Sasaki in a nearby park. This time, Low did not return; his son testified to seeing his body floating in the river.[3] However, it was never established in court as to why Low was detained twice; it seemed he had simply become a suspect.

Ong and Low’s stories are representative of the numerous incidents of torture documented within the war crimes cases. A collective reading yields an overwhelming sense of random suddenness. Koh Soo Keng for example was arrested on 14 August 1944 while at the park and later subjected to four months detention and torture. Of his ordeal he said, “I was not told the reason, but I was asked to admit and I did not know what to admit.”[4] Like Koh, many victims were baffled as to why they were persecuted; few admitted to acts of resistance or heroics. One would imagine that it would have been advantageous for victims to admit they had been involved in anti-Japanese activities or had harboured pro-British attitudes. Instead most exhibited hapless ignorance. Lim Guet Keow for instance was arrested at her home in November 1942 and tortured in a cell adjoining her husband’s. Her husband died after two months of incarceration. When asked why they had been arrested, she answered simply, “I was not told for what reason.” When pressed as to whether her husband had been involved in any subversive activities, she was adamant, “No Sir, my husband didn't join any [secret] society.” What about her, had she been involved? “No, Sir. Never mixed up with any friends,” she claimed, “always in the home.”[5] Similarly, Yu Song Moi recalled how, along with 26 others, she had been arrested in January 1945. After months of torture, she was admitted to Sibu Hospital. When asked if she knew why she had been arrested, she replied, “As far as I know, no reason at all.”[6]

Kempeitai procedure, it seems, involved casting the net of aspersion far and wide, often abetted by baseless accusations from local informants, only to whittle down the throngs of guileless suspects through a systematic escalation of abuse. The prized objective was intelligence, be it admission of wrongdoing or providing potential leads on subversive activities. When coercion and abuse failed to produce a confession, attempts often turned towards cultivating the victim as a future informant, thus perpetuating the cycle of (mis)information. Lam Keong Kong for instance was arrested with his father, mother, uncles, brother and sister-in-law. He was suspected of hiding firearms for the resistance. After six months of torture, when the Japanese were satisfied that there was nothing to be elicited from Lam, he was released. During this time, two of his family members died in custody while the rest went missing. According to Lam, he had been released on condition that he report back periodically to provide information on suspected communists. The accused however provided conflicting testimonies on Lam’s involvement with the kempeitai: one claimed that Lam had become friendly with his previous torturers on his own accord, even inviting them home to dinner and lending 200 yen to another; another attested that Lam had served as an orderly to the station’s staff sergeant while in detention, which was unusual for prisoners; and yet another denied Lam was ever an informant or under kempeitai employ.[7] Lam stated that he was “forced to have a friendship” with the kempeitai and admitted he had received “favourable treatment” after his release, including gifts of rice.[8]

Kempeitai officers were under immense pressure to produce intelligence, no matter how dubious the methods employed or the information obtained. Sergeant Shin Shigetoshi testified that his commander had demanded “information and results at all costs;” failure to do so, he claimed, was tantamount to insubordination which was a punishable offence.[9] Similarly, Lim Say Chong, a Chinese clerk at the Ipoh kempeitai office, overheard the officer-in-charge Anraku Chosaku order two Taiwanese interpreters to extract information from a prisoner. Anraku allegedly told the men: “Take him away, must get a confession out of him even if you have to kill him.”[10] The suspect, Foong Koon Hoy, subsequently died as a result of water treatment.

Victims often caved in and confessed to crimes they knew little about. Some even went to extreme measures to satisfy their torturers. Lam Nai Fook affixed his thumbprint to three statements he was given, even though he admitted: “I was made to sign but what were the contents I do not know.”[11] Tan Cheng Chuan was similarly perplexed. The Japanese had accused him of being involved with the resistance. After days of torture, a Chinese detective, Chia Koon On, urged him aside to confess lest he be beaten to death. Whether Chia had Tan’s interest at heart is unknown but Tan eventually confessed that he was a communist. “Then the Japanese gave me a cigarette,” he recalled. “They asked me to which communist I belonged to so I answered the Triangle Communist. In fact I don't know what Triangle was, I bluffed them.”[12]

While torture was endemic, several accused steadfastly denied that kempeitai policy advocated abuse.[13] Others offered conflicting testimonies.[14] Among them, Sergeant Major Otoda Hiroshi’s deposition stands out as he was the only individual, among a total of 162 accused, who pled guilty to the charges levied against him. Otoda however justified his plea; he had merely discharged his duties according to “the policy of the kempeitai and living up to its traditions to the best of my ability” and he sincerely believed that his “treatment of [the victims] was for the common good.”[15] During cross examination, he described plainly the interrogation methods practised at the Alor Setar police station. These were summarised during the prosecution’s closing address:

…beating and poking with sticks, kicking, slapping the face with hands or slippers, suspending upside down, suspending by the wrists tied behind the back, burning with hot strips of metal or cigarette ends, water torture – victim placed on his back, flannel over his face, water is played from a hose attached to a tap, and water is sucked in, this continues until the victim’s stomach is filled with water and distended, sometimes a plank is placed upon the stomach and pressed or stood upon until the water is forcibly expelled.[16]

The methods employed at Alor Setar were common practise.[17] Clearly, these abusive techniques were either well established and therefore sanctioned, or widely shared and therefore encouraged. Euphemisms were often used to describe various torture methods, as in ‘water treatment’ or ‘electric treatment.’ They differed only slightly from field office to field office; ‘water treatment’ for example could mean dunking the victim’s head into a basin of water,[18] placing the victim’s head face upwards under a flowing tap,[19] submerging the victim upside down inside a tank filled with water[20] or lowering the victim into a well.[21] However, at times, rather bizarre methods were also employed. In Penang, torturers often flung the station’s pet monkey at suspects during interrogations.[22] In Kota Bahru, Ho Chid’s fingernails were extracted; he was then wrapped in barbed wire and rolled about on the floor.[23]

Abuse was steadily escalated when a suspect proved uncooperative. Lim Nai Meng’s story is a prime example. He was arrested on suspicion of having organised an anti-Japanese unit. After repeated beatings over several days which rendered him semi-conscious, he was suspended from the ceiling with ropes tied to his thumbs until “the bones inside it could almost be seen.”[24] Burning papers were applied to his buttocks, legs and private parts. Intermittently, between beatings, he was submerged in a water tank. When returned to his cell, his hands were bound for fear that he would commit suicide. Nevertheless, Lim was found one morning with his tongue bitten off. He had expired without divulging a single piece of useful information.

For those who withstood torture their ordeal did not stop as long as they remained in captivity. Ultimate survival depended on their capacity for endurance, as rations were scarce, medical attention inadequate and detention cells vermin-infested. Some prisoners proved resilient, such as Low Kiang Pin, who endured 10 months of torture until liberation on 6 September 1945.[25] Many were less hardy, succumbing to a combination of torture, illness and deprivation. How many endured captivity is inconclusive as Japanese record-keeping was erratic, highly inaccurate and most records were destroyed.

The situation at Penang Prison is illustrative. Available records admitted into evidence reveal large gaps, most notably between March 1942 and March 1944, when registrations of death were suspended.[26] It was estimated however that the death toll throughout 1943 averaged 10 to 15 a day.[27] Available records dating between 22 March 1944 and 24 August 1945 indicate that 589 persons met their demise. Of these recorded deaths, 15 were ascribed to hanging while the rest were attributed to illnesses, from beriberi, tuberculosis, septicaemia to even senility.[28] Whether these deaths were hastened by complications arising from torture is unknown. Evidence suggests medical officers were often instructed to downplay prisoners’ health conditions or falsify the causes of death.[29] Hence, deaths attributed to illness belie potential ill treatment. When Lee Teck Hua retrieved the body of his son at Outram Road Jail, he was convinced that Lee Tee Tee had been “beaten to death” for he was “beaten until unrecognisable.”[30] He had to rely on a clerk to point out the body. The death certificate however stated the cause of death simply as beriberi.[31] This suggests that even when documentation exists, it may present only a partial picture of reality. As further proof, it should be noted that records of the 15 Chinese who were allegedly hung in Penang Prison span only three months, from June to September 1944.[32] It is dubious there were no other hangings before or after this period. Similarly, between 22 September 1942 and 10 August 1943, only two Indians, three Malays and 13 Chinese were reportedly executed.[33]

According to Corporal Bhag Singh, the Indian head of security at the prison, there were at least 1,500 prisoners in 1942 alone. While 500 were released, many died from starvation. By April 1943, Singh testified that the “120 that were left were just about to die.”[34] Corroborating testimonies from Malay and Indian sub-warders suggest that the prison population remained substantial throughout the occupation. There were three primary halls with multiple cells. Each cell held between 15 and 20 prisoners. Hall A and B were reserved for Chinese prisoners, while Hall C, which had 104 cells, had a mixed population of Chinese and Indian inmates, among them up to 800 women.[35] The women were subjected to similar ill treatment as the men. Indian medical officer Govindasamy recalled seeing female corpses in the hospital mortuary, where “the women were very thin, emaciated and their legs swollen up.”[36] Cecilia Wong, a Chinese matron attached to the women’s ward at Penang Hospital, recalled attending to Wong Kah Foong in October 1943 and Hwa Lan in February 1944.[37] Both had been tortured; one woman alleged she had been stripped, tied up and her genitalia prodded with a stick. In Kajang prison, Chen Foh Shin testified that during his incarceration, he knew of one cell that housed only women inmates.[38] At the Ipoh kempeitai office, Leong Sie Chun recounted how a female prisoner of 20 had been stripped naked during an interrogation, her breasts pierced with wires and her genitalia scorched.[39]

The only available records on deaths at Penang Prison list the 589 victims by name. Apart from these identified prisoners, it is impossible to know for certain who or how many were incarcerated, let alone how many were lost. Corpses were disposed of at multiple mass burial sites. Chinese caretaker Goh Teng Leong was among several employed to remove bodies from the prison and bury them at Rifle Range near Kampung Bahru. He testified that on average, he buried between three and six bodies a day. When asked what was the most he ever buried in a day, he replied, “five, six, seven or eight, I am not certain.”[40]

Another mass burial site was Bukit Dunbar on Thien Eok Estate. When this site was discovered by the War Crimes Investigation Unit No. 6, a partial excavation was undertaken. One mass grave measuring 50 feet in length and three feet wide was opened up to a depth of six feet, even though it was estimated that the grave was possibly 10 feet deep or more. Major Douglas Hayhurst counted 232 skulls, after which the remains were reinterred in situ. He also testified that there were at least three mass graves on the site but these were not disturbed.[41] Even though the prison population was not exclusively Chinese, it appears that the authorities assumed that since the majority of victims were Chinese, there was no need to consult anyone but local Chinese associations about this discovery. Furthermore, the value of the site as visual and physical testament of Japanese atrocities was not lost on the administration. Photos of the exhumations were provided to the Chinese press even as the trial was underway.

Persecution by the kempeitai was not restricted to suspects. Often, family members were also abused to compel the suspect to talk. Dr. Sybil Kathigasu, of Eurasian ethnicity, endured needles stuck under her fingernails and canes pressed into the sockets of her kneecaps. She was also burned with heated iron rods and hung upside down and beaten. Yet she refused to admit she had provided medical assistance to guerrillas. The kempeitai changed tack; they strung up her 7-year-old daughter in a tree and lit a fire beneath her. Kathigasu stood firm; she knew that if she spoke it would mean “death for thousands of people up in the hills.”[42] Unable to break her, the kempeitai released her daughter but turned their attention to her husband. Under torture, he broke down and Kathigasu was sentenced to life imprisonment. In another incident, Tham Keng Yam’s father was escorted to his residence and subjected to water treatment in front of him, after Tham denied owning a radio set. They were both beaten and incarcerated. Tham was asked to identify his father’s body and released. Tham was simply told, “Your father’s case is over and you are free now.”[43] Like so many others, Tham had no recourse; it was just the way things were.

The picture of the occupation that emerges from the trial cases is one of a deep and hopeless malaise. Many appear to have succumbed to apathetic helplessness or bewildered disconcertment. When violence occurred in their midst, they were reduced to meek onlookers. When violence was visited upon them, there was hapless resignation. Never was this more evident than in cases involving random and sudden violence. The plight of Anis bin Elok is a prime example. A stranger to Sibu, the Malay man had wandered into the town. As he was passing the police station, he heard the cries of a man being tortured and entered the premises to enquire. For his curiosity, he was strung up and beaten and his torturers left him tethered to the ceiling. When they returned an hour later, he had expired. Anis’ body was cut into pieces and thrown into a nearby river.[44] In Rengan, Chong Chuan’s husband was rounding up their drove of pigs for the night. Without warning, a report rang out in the dark. Her husband, Hee Than, was killed by Hayashi Sadahiko with a single rifle shot from 20 feet away. Chong was cautioned to not report the incident on pain of death.[45] In Melaka, Tay Kiam Aik was arrested and brought to the police station. The Chinese man appeared to be of unsound mind; when questioned, all he did was laugh. Tay was promptly beheaded, his head placed in a wooden box and displayed at a road junction.[46] In Perak, Tan Lim’s son was bundled into a car by several Japanese officers. He followed on his bicycle and saw his son taken into a shop. Several hours later, Tan Put Kim was escorted to the back of the premises next to a river. Tan Lim then heard the sound of gunshots and watched his son’s body float away.[47] In Bentong, Tan Ching Leong was escorted between a Japanese officer, Shima Nobuo, and a local interpreter. The party marched up Ah Peng Street, where they met with another Japanese officer named Wada. The district officer was a Malay man known as Dato’ Hussein, who had been in a meeting with Wada. He testified that the officers exchanged a few words, following which, Shima “unsheathed his sword and executed the Chinese with one stroke.”[48] The beheading was perfunctory and accomplished with aplomb. It was witnessed by local residents, who kept their heads down and went about their business.[49] Tan’s corpse was left in the street until midday.[50]

The Japanese army displayed similar equanimity in the commission of wholesale slaughter. In Negeri Sembilan, officers of the 11th Regiment of the 25th Army were instructed to “summarily execute any Chinese found in their areas.”[51] On 10 March 1942, a force of 70 soldiers arrived into Senaling. They arrested four prominent Chinese families and an indeterminate number of Chinese. The men, women and children were taken to Kuala Pilah by lorry. Behind the town’s former English school, they were bayoneted and cut with swords. Four days later, the regiment returned to Senaling where Captain Iwata Mitsugi briefed the assembled villagers. He announced that the four families would not be returning. Their belongings were given to a Malay villager to auction. On their way out of the village, the regiment rounded up 76 Chinese refugees who had been squatting in the market and marched them to Kuala Pilah. Once there, some were released while the majority met the same fate as the previous victims. The following day, the same regiment marched into the nearby town of Parit Tinggi and assembled the villagers under the ruse of dispensing safe passes. The 675 men, women and children were despatched in the surrounding vicinity and the village was set alight.

Sporadic lightning raids on homes, villages and businesses were recorded throughout the occupation.[52] These operations were intended to weed out anti-Japanese guerrillas, turn up outlawed items or punish anyone suspected of providing support to the resistance. In an unusual case, the Chinese village of Sungei Lui was raided in August 1942 purportedly to search for a missing Malay man named Zakanah bin Bassir.[53] The significance of Zakanah was not established in court. The men were shot in batches of 10, while the women and children herded into a shop where they were machine-gunned. In Tenghilan, during a raid on Chau Kee Sundry Shop in October 1943, the proprietor was found in possession of a Nationalist Chinese flag and summarily executed.[54] A search for “Chinese agitators” on Mentanani island in February 1944 led to the mass killing of 60 Suluk men, women and children, and several Chinese.[55]

Sometimes, the objective of the lightning raids was unclear. In the village of Kuala Kubu for example the villagers were preparing for a wedding on 28 April 1944 when a contingent of soldiers arrived and fired a shot into the air. The villagers fled helter-skelter. Seven Chinese men were herded into a house, bayoneted and the house was set on fire.[56] When asked why the villagers had been targetted for Japanese action, Lei Kow, one of the surviving victims, replied, “I do not know the cause.” When asked by the defence counsel if he had been “in league with the notorious Chinese bandit Communist Party?,” Lei Kow denied this. “No, not so,” he answered, “I devoted all my time to planting food crops. I have a lot of children.”[57] The defence counsel’s attempt to paint the victims as anti-Japanese was unsuccessful. Similarly, in December 1944, a 30 man-strong detachment comprising Japanese officers and Indian, Malay and Chinese sub-police, raided the Soon Foh mine in Kampar. The coolies were asked if there were any anti-Japanese people on site.[58] When no one stepped forward, the coolies were beaten, and the staff quarters and machinery set on fire. Why did the Japanese scupper production at the mine? It is highly unlikely that their aim had been to disrupt output. There appeared to have been little tangible benefit to such operations except to keep the populace on edge.

In 1945, as the tide of war began turning against the Japanese, there was a corresponding escalation in atrocities. The highly-charged atmosphere bordered on paranoia; any whiff of dissent or suspected infraction was met with swift reprisals. Civilians careless enough to let slip that a future Allied victory was imminent were accused of spreading propaganda and summarily disposed of.[59] Repressive measures were stepped up to tighten security and maintain control. In Kampar town for example 40 to 45 “beggars” – most likely displaced persons or refugees – were trucked to the outskirts in early 1945 and shot; in May, several Chinese teens suspected of theft were executed without trial; in June, Chinese farmers who were clearing jungle foliage without obtaining prior permission were machine-gunned on site; that same month, a Malay man, Ali Zaman, was executed for “blasphemy” against the emperor; and in August, six pork sellers and several others were rounded up in the town market for “spreading communist propaganda” and shot.[60]

From mid-1945 onwards, there were concerted efforts at eliminating witnesses and destroying evidence. Captain Harada Kensei testified that in preparation for imminent Allied landings, the Jesselton kempeitai had received the order to implement the “Third War Plan.” This, he said, involved “clearing out all elements detrimental to the peace,” including blacklisted persons and suspects in custody.[61] The existence of a ‘Third War Plan’ has not been raised in any known academic discourse on the Japanese occupation nor did any other accused mention it. Nevertheless, it is clear that ‘clearing out’ activities accelerated during this time. In Keningau, prominent civilian internees were marched to Renau and executed by firing squad in July 1945. They included the British Chief Secretary, Silis Drummond Le Gross Clerk, rubber plantation owner Ronald Macdonald, American engineer Henry William Webber, Dr. Valentine Alexander Stookes and the Chinese Consul-General, Cho Huan Lai.[62] That same month, 17 Chinese internees at Bentong police station were trucked to the 11th mile Karak Road and killed.[63]

Elimination operations continued even after the Japanese surrender on 15 August. Between late August and early September 1945, the cells at Kampar police station were emptied out. Malay constables testified that the Chinese prisoners were shot in batches in the neighbouring hills.[64] On 5 September in Melaka, 14 Chinese civilians were arrested from among 50 who had gathered at the Overseas Chinese Association building. They were spirited away to a remote island where they were bayoneted and thrown down a well.[65] Having heard of the Japanese surrender, they had gathered to discuss future plans for the community. While the atrocities described in some detail above are not exhaustive, these multiple accounts, it is hoped, convey in some limited measure the destitution and degradation unleashed during the occupation. Wives were left to dig for the bones of their husbands on the beach;[66] fathers fished their sons’ bodies out of rivers;[67] while strangers disposed the corpses of unknown dead.[68] Meanwhile, profiteers flourished in the black market, women canoodled with Japanese officers at dance halls, desperate mothers scavenged for food, and scores of orphaned feral children roamed the streets, even as informants exchanged accusations for favours.

Such abnormal times were made possible by the undercurrent of chronic terror which ran beneath the surface of normal living. In maintaining a violent hegemony, the Japanese administration was aided by local Chinese, Malay, Indian and Eurasian auxiliary policemen, translators, jailers, mortuary hands, doctors, sub-wardens – and the list is large for those who made up the cogs of the occupation machinery – who, while often reluctant, were obsequious servants. Many felt fear and in turn perpetuated fear. The participation of collaborators, as the historian Timothy Brook has pointed out, allows for the narrative of atrocity in war to be normalised.[69] Those in Japanese employ inadvertently legitimised and maintained the Japanese system of terror.

[1] Prosecutor’s Closing Address, WO235/877: Trial of Anraku Chosaku, Kampar, 20-21 June 1946, TNA.

[2] WO235/872: Trial of Sgt. Maj. Toyoda Akiichi, Singapore, 3-8 July 1946, TNA.

[3] Testimony of Low Thiong Mong, WO235/866: Trial of Sgt. Sasaki Saburo, Telok Anson, 17-18 June 1946, TNA.

[4] Testimony of Koh Soo Keng, WO235/819, TNA.

[5] Testimony of Lim Guet Keow, WO235/819, TNA.

[6] Testimony of Yu Song Moi, WO235/890: Trial of Lt. Murakami Seisaku and three others, Singapore, 14-17 August 1946, TNA.

[7] Testimonies of Hase Ryosuke, Murata Yoshitara and Shin Shigetoshi, WO235/819, TNA.

[8] Testimony of Lam Keong Kong, WO235/819, TNA.

[9] Testimony of Shin Shigetoshi, WO235/819, TNA.

[10] Testimony of Lim Say Chong, WO235/877, TNA.

[11] Testimony of Lam Nai Fook, WO235/819, TNA.

[12] Testimony of Tan Cheng Chuan, WO235/872, TNA.

[13] See for example testimonies from: Maj. Onishi Satoru, Sgt. Uekihara Susumu and Sgt. Matsumoto Mitsugi, all three were based at the kempeitai headquarters in Oxley Rise, Singapore; WO235/843, TNA.

[14] In the same trial as above, i.e. WO235/843, other accused provided convoluted testimony as to what methods were employed. Most agreed that physical abuse was used but either denied engaging in such acts themselves, or that abuse was perpetrated only when interrogators had run out of options. See testimonies from: Sgt. Matsumoto Mitsugi and Sgt. Shimomura Tomohei.

[15] Appendix ‘E’: Petition against the Sentence of a Military Court, 11 February 1946, WO235/815, TNA.

[16] Prosecuting officer’s closing address, WO235/815, TNA.

[17] For example, Sgt. Nishi Yoshinobu, who was based in the Kuala Lumpur kempeitai office, describes similar torture methods. See: Evidence ‘A’: Summary of Examination, 24 June 1946, WO235/870, TNA.

[18] Testimony of Tham Keng Yam, WO235/821: War Crimes Trial of Sugimoto Heikichi and two others, Singapore, 5-7 February 1946, TNA.

[19] Testimony of Low Kiang Pin, WO235/819, TNA.

[20] Testimony of Sithamparam Pillay Karthigesu, WO235/953: Trial of Ogata Tsuyoshi, Kota Bahru, 21-24 October 1946, TNA.

[21] Testimony of Bhag Singh, WO235/931, TNA.

[22] Testimony of Syed Mohd, WO235/931, TNA.

[23] Testimony of Sithamparam Pillay Karthigesu, WO235/953, TNA.

[24] Testimony of Chong Seng Ee, WO235/872, TNA.

[25] Testimony of Low Kiang Pin, WO235/819, TNA.

[26] Testimony of Sheikh Ahmad Jelani, WO235/931, TNA. Sheikh Ahmad Jelani was the deputy registrar of births and deaths at the prison hospital. His testimony is corroborated by Corporal Bhag Singh who claimed that deaths in the prison were not recorded in 1942 and 1943, but that record-keeping resumed in 1944.

[27] Testimonies of Dr. Randmangan Letchmanasamy and Abbas Hussein bin Bacha, WO235/931, TNA.

[28] Evidence ‘J:’ List of Deaths in Prisons (Penang) Registered at General Hospital Penang, WO235/931, TNA.

[29] See for example: Testimony of Ayadurai, WO235/843, NA. Ayadurai, a senior dresser at Outram Road Prison hospital was tasked with recording admissions; he testified that “Mikizawa, the Japanese Commandant, was always objecting to persons being stated to be other than in good condition” even though “with very rare exceptions, no prisoner was ever in good condition.” The death of Ngu San Tieh was recorded as due to natural causes even though he died while being tortured; see: Testimony of Victor Francis Xavier, WO235/878: Trial of Sase Yoriyuki, Singapore, 17-19 July 1946, TNA. The death of Lall Singh Bull was recorded as an accident, though he too died while being interrogated; see: Testimony of Gorbex Singh, WO235/870, TNA.

[30] Testimony of Lee Teck Hua, WO235/843, TNA.

[31] Testimonies of Lee Keok Seng, WO235/843, TNA.

[32] Evidence ‘H:’ Return of Deaths in the Penang Prison from 1.1.1944 - 3.9.1945 (Jud: Hanging), WO235/931, TNA.

[33] Evidence ‘G:’ Deaths (Executions) from 1.6.42 – 14.2.44, WO235/931, TNA.

[34] Testimony of Bhag Singh, WO235/931, TNA. On the prison population and conditions, see also corroborating testimonies from sub-warders Kassim Ali bin Hashim, Ismail bin Mat Taib, Hashim bin Arshad and Abbas Hussein bin Bacha.

[35] Testimonies of Hashim bin Arshad and Hashim bin Kaji Kadar, WO235/931, TNA.

[36] Testimony of Govindasamy, WO235/931, TNA.

[37] Testimony of Cecilia Wong, WO235/931, TNA.

[38] Testimony of Chen Foh Shin, WO235/830, TNA.

[39] Testimony of Leong Sie Chun, WO235/837, TNA.

[40] Testimony of Goh Teng Leong, WO235/931, TNA.

[41] Testimony of Douglas Hayhurst, WO235/931, TNA.

[42] Evidence ‘C’: Affidavit of Sybil Kathigasu, WO235/837: Trial of Sgt. Yoshimura Ekio, Ipoh, 18-20 February 1946, TNA. Upon liberation, Kathigasu was sent to London for medical treatment. She was awarded the George Medal in 1947. However, before she could return home, she succumbed to septicaemia and died. Her story is documented in her memoir, No Dram of Mercy.

[43] Testimony of Tham Keng Yam, WO235/821, TNA.

[44] Testimony of Jackie Young, WO235/878, TNA.

[45] Testimony of Chong Chuan, WO311/543, Case No. 65225: Trial of Sgt. Hayashi Sadahiko and Toriumi Mamoru, Johore Bahru, 2-12 July 1947, TNA.

[46] Testimony of Ali bin Sidan Idin, WO235/888: Trial of WO Osaki Giichi and two others, Melaka, 26-27 August 1946, TNA.

[47] Testimony of Tan Lim, WO235/866, TNA.

[48] Testimony of Dato Hussein, WO235/881: Trial of Sgt. Maj. Shima Nobuo, Bentong, 15 July 1946, TNA.

[49] Testimonies of Ho Swee Kei, Wong Chun, Chia Ah Fah and Ng Hai Chew, WO235/881, TNA.

[50] Testimony of Tan Cheow, WO235/881, TNA.

[51] Abstract of Evidence, WO311/543, Case No. 65272: Trial of Capt. Watanabe Tsunahiko and two others, Kuala Lumpur, 22 Sept ember-13 October 1947, TNA.

[52] For other raids, see: Swee Radio Service, a shop in Bukit Bintang Road in Kuala Lumpur, in November 1943, WO235/904, TNA; Khoo residence, Singapore, in October 1943, WO235/907: Trial of Sgt Okayama Hikoji, Singapore, 25-26 June 1946; multiple raids on Pinji Estate including July 1945, WO235/845: Trial of Nagayasu Mamoru, Ipoh, 1-2 May 1946, TNA; Bukit Koman in May 1944, WO235/873: Trial of Sgt. Maj. Tanaka Hideo, Raub, 18 July 1946, TNA; Raid on Cho residence, Brinchang, in June 1945, WO235/866, TNA.

[53] WO311-543, Case No. 65275: Trial of 2nd Lt. Hashimoto Tadashi , Kuala Lumpur, 21-29 July 1947, TNA.

[54] WO235/926: Trial of Kato Chuichiro, Borneo, 20-22 November 1946, TNA.

[55] WO235/882: Trial of 2nd Lieut. Shimizu Kiyogi and seven others, Singapore, 15-29 July 1946, TNA.

[56] WO235/824, TNA, 14.

[57] WO235/824, PRO, 14.

[58] Testimonies of Yeong Choy and Cheong Hon Leong, WO235/877, TNA.

[59] Such incidents were recorded in Penampang, Telipong, Menggatal, Kuala Belait and Jesselton between June and July 1945; see: WO235/884: Trial of Capt. Harada Kensei, Singapore, 8-11 July 1946, NA, and WO235/833, TNA.

[60] Testimonies of Lall Singh, Soo Peng Hui, Tan Teck Oi, Niaz Mohamed and Seah Chong Sin, WO235/877, TNA.

[61] Testimony of Capt. Harada Kensei, WO235/928, TNA.

[62] WO235/883: Trial of Lt. Col. Abe Kiichi and three others, Labuan, 29 April-4 May July 1946, TNA.

[63] WO235/880, TNA.

[64] WO235/877, TNA.

[65] WO235/875: Trial of Capt. Kamezawa Matsutoshi and ten others, Melaka, 5-6 July 1946, TNA.

[66] Testimonies of Edith Chong and Mrs Leong Chong Fah, WO235/833, TNA.

[67] Testimonies of Tan Lim, Low Thiong Mong and Beh Chin, WO235/866, TNA.

[68] Testimonies of Tham Heng, WO235/880, NA; and Lee Ah Fong, WO235/926, TNA.

[69] Timothy Brook, Collaboration: Japanese Agents and Local Elites in Wartime China (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2007), 242.