SOOK CHING MASSACRES in malaya

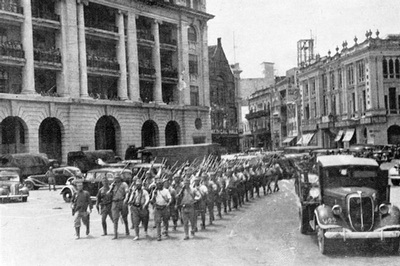

On 8 December 1941, an hour and a half prior to the bombing of Pearl Harbour, the Imperial Japanese 25th Army invaded the northeast of the Malay Peninsula. Thus began the conquest of Malaya which would see Britain “forfeit the dignity of one hundred and twenty years.”[1] After a campaign lasting 70 days, the British forces surrendered unconditionally at Singapore on 15 February 1942. Two days later, General Tomoyuki Yamashita gave the order to conduct shukusei (cleansing) activities against ‘undesirable’ elements, ranging from suspected criminals, communists to pro-British and anti-Japanese individuals.[2] The order was interpreted by officers and soldiers in the field as “a licence for summary killing,” thus triggering the sook ching massacres.[3] While this order did not amount to the sanguang or ‘three all’ policy (kill all, burn all or loot all) practised in China, it nevertheless wreaked immeasurable havoc.

Among the Malayan population, the Chinese population in particular was regarded as suspect and treated as such. During the cleansing operations, Chinese civilians – primarily men aged 18 to 50, though in many cases women, children and the elderly as well – were ordered to assemble at various public spaces, temporary screening centres or detention camps, sometimes for hours or days, without food and water. Some thought they were meant to register for work or ‘safe’ passes. In other cases, a ruse was used to encourage compliance. In Taiping, the town’s inhabitants were told to gather to receive favourable news.[4] They were then screened. Those who ‘passed’ were released, those who ‘failed’ were taken away; many were summarily executed, others disappeared. Similar scenes were played out across the territory: at a screening centre in Johor Bahru, one in five were taken away to dig their own graves at the Civil Service Club, others were machine-gunned along the seafront; in Malacca, around 90 members of the Straits Settlement Volunteer Forces (SSVF), including five Malay officers, were assembled along three trenches and shot; in Singapore, those killed at Changi Beach were so numerous that it took almost three weeks to bury their bodies.[5]

A typical screening scene involved filing past a Japanese officer, and beside him, a hooded or masked informer or sometimes a known Japanese resident.[6] The identities of the informers remain open to speculation. Some believed them to be renegade Taiwanese or Japanese agents, captured triad members, or simply individuals seeking revenge for past wrongdoings or favours with the new administration. At times, questions were asked about language, schooling and residence. Other times, the assembled were sorted en masse, by a show of hands or by category: civil servants, students, petty hawkers, and so on. In some cases, no words were exchanged, a cursory glance was all that was required; those with tattoos were thought to be triad members, while those from the Hainanese dialect subgroup were assumed to be communists. The educated – civil servants, lawyers and teachers – were also considered threats. Wearing spectacles was taken to be indicative of intellectual status. Thio Chan Bee recounted how he narrowly escaped by ignoring the order to assemble at the Jalan Besar camp in Singapore. There, two of his less fortunate but equally bespectacled colleagues were never seen again.[7]

The number of victims killed during this period has not been ascertained. In Singapore alone, 70,699 were captured; the number of survivors is unknown. Japanese propaganda justified these actions as a preemptive strike against anti-Japanese and criminal elements.[8] Details of massacres on the Malayan peninsula during this time are fragmented. It appears that villages, towns and cities with large Chinese populations were particularly affected. In some cases, the inhabitants of entire villages, such as those in Simpa, Parit Tinggi, Jelulung and Johol, were massacred.[9] In these locations, screening operations were dispensed with; men, women and children were simply rounded up and killed.

Scholars have since debated the severity and causes of the sook ching massacres. In his analysis of the Malai Gunsei or Japanese military administration in Malaya, Japanese historian Akashi Yoji concludes that, despite initial proposals to solicit Chinese cooperation, “the voice of moderation fell by the wayside.”[10] He fingers Watanabe Wataru, the deputy chief of the gunsei, as the primary voice of excess. According to Akashi, Watanabe’s previous experience of guerrilla resistance in China convinced him that the “crafty as anything and hard to control” Chinese “should be dealt with unsparingly.”[11]

Other historians have suggested that the last-stand battle for Singapore played its part in precipitating the massacres. During the siege, Japanese forces met with tenacious but ineffective defence on the part of Chinese irregulars of the SSVF. These volunteers had been called upon only two weeks before the Japanese arrival and were barely trained and poorly armed. Despite this, Ian Morrison, the Australian war correspondent for The Times, observed that they “put up a good fight” for “they had what the Indian and Malay troops lacked, personal venom against the Japanese, who for four years had been killing their fellow countrymen in China.” However, rather presciently, Morrison also predicted that this could lead to “terrible reprisals once the Japanese armed forces were in full control.”[12] Several historians, among them Cheah Boon Kheng, Paul H. Kratoska and Yap Hong Kuan, concur with Morrison’s view.[13]

Japanese historian Hayashi Hirofumi however refutes that the massacres were retaliatory, pointing to the lack of corroborative Japanese sources to substantiate this conjecture. He argues instead that the massacres were a progressive escalation of tactics adopted in China, pointing to Yamashita, who led the invasion forces, as “the link that connected Japanese atrocities in Manchuria and North China with those in Singapore.”[14] In his prior posting as Chief of Staff of the North China Army, he had become acquainted with Watanabe, then head of the Tokomu Kikan espionage unit. Hayashi suggests that Yamashita and Watanabe were staunch supporters of genju shobun (harsh disposal) and genchi shobun (disposal on the spot) methods honed in Manchukuo and north China. Yet others have pointed to Masanobu Tsuji, who headed the Doro Nawa research unit and was subsequently operations officer of the invading 25th Army, as the mastermind behind the Chinese massacres.[15]

The massacres triggered a series of unforeseen consequences. Many Chinese fled the cities for the interior, thus depressing trade and industry further. Others became incentivised to join guerrilla groups in the jungles, among them “rubber-tappers, tin-mining coolies, and vegetable gardeners,” not because of ideological motivations but just so they could “‘have a crack at the Jap.”[16] Kratoska has suggested that the intent of the massacres may have been to “bludgeon the entire Chinese population into submission;” however, its effect was to generate “hatred among people who might otherwise have acquiesced to Japanese rule.”[17] In response, the Chinese adopted a “recalcitrant and intransigent attitude” which “inspired still more harsh methods of repression.”[18] Attempts in late 1943 to pacify the Chinese by integrating them into business, education and government advisory councils could not breach these initial hostilities; instead, “the Chinese reciprocated with non-cooperation and resistance.”[19]

In his unpublished memoirs, Major General Fujimura Masuzo, who succeeded Watanabe in 1943, emphasised the perennial Chinese thorn in the side of the Japanese military administration. The Malai Gunsei he opined was in actuality a Kakyo Gunsei or Overseas Chinese administration. Its duties were hindered by the continuous need to deal with the Chinese for “it was the Kakyo who organised an anti-Japanese army, the Kakyo who cooperated with the gunsei, and the Kakyo who opposed cooperation with the gunsei.”[20] Just like the British before them, the Japanese had to contend with the shifting sands of factionalised Chinese allegiances.

Additional Notes

The prominence of the sook ching massacres in historical discourse has inadvertently promoted several misperceptions. The first concerns the extent of the shukusei or cleansing operations. Thus far, academic attention has been predominantly focussed on events in Singapore. This is not necessarily the result of scholarly neglect. Shukusei was initiated in Singapore before ‘mopping up’ operations moved up the peninsula. It was in Singapore that the magnitude of its effects was most felt, owing to the size of the Chinese population relative to other ethnic groups, and in full view of witnesses, which produced multiple corroborating accounts. Further, these killings achieved a measure of sensationalism during the Singapore Chinese Massacres Trial after the war.

In contrast, shukusei operations on the peninsula have become peripheral to the main event in Singapore. It is only belatedly that historians have linked other mass killings on the peninsula to the sook ching. [See for example: Geoffrey C. Gunn’s article “Remembering the Southeast Asian Chinese Massacres of 1941-45” in Journal of Contemporary Asia 37, 3 (2007): 273–291]. As a result, the first known massacre in Pasir Puteh on 20 December 1941, shortly after the initial Japanese landings off the coast of Kelantan, has been recognised as a “prelude or testing ground” for the purge which came after. There, Chinese male inhabitants were asked to assemble after which five were executed for refusing to hand over the local branch’s China Relief Fund ledgers. Accounts of massacres in other locations from February to April 1942, such as those which occurred in Penang, Kuala Lumpur, Negeri Sembilan and Johor have been documented, though they too have received less detailed attention. Consequently, knowledge of shukusei operations on the peninsula is piece-meal; they do not evoke a similar spectre to the sook ching massacres in Singapore.

Further, disproportionate attention to the sook ching massacres appears to imply that other atrocities were neither significant nor prevalent. Archival research of the war crimes trials refutes this perspective. In terms of geographical distribution, atrocities were documented throughout the Malay Peninsula, Singapore and British Borneo. The scenes were varied, from remote villages to larger towns and cities. The alleged crimes span the duration of the occupation, from February 1942 to September 1945, with little temporal reprieve from violence. The final months were particularly intense amid concerted efforts to eliminate blacklisted persons, potential witnesses and suspected political agitators. Atrocities persisted in the interim between the Japanese surrender on 15 August 1945 and British reoccupation several weeks later.

[1] Masanobu, Japan’s Greatest Victory, xvi. For a more recent analysis of Japanese military strategy in this campaign, see: David J. Mollahan, et. al., The Japanese Campaign in Malaya: December 1941-February 1942, A Study in Joint Warfighting (Norfolk: Joint Forces Staff College, 2002).

[2] It should be noted that Yamashita denied knowledge of the purge conducted in Singapore. He blamed the commander of the Kempeitai but could not remember the name of the officer. See: Report on Interrogation of General Tomoyuki Yamashita by Major C.H.D. Wild, “E” Group, SEAC at Manila, 28 October 1945, WO325/30, TNA.

[3] Bayly and Harper, Forgotten Armies, 211.

[4] Cheong Peng Yeap, “Sejauh Manakah Pendudukan Jepun di Taiping Mempengaruhi Kehidupan Seharian Komuniti Cina di Sana?” [To What Extent Did the Japanese Occupation Affect the Daily Life of the Chinese Population in Taiping?] (Essay, Penang: Universiti Sains Malaysia); quoted in Kratoska, Japanese Occupation, 99.

[5] Bayly and Harper, Forgotten Armies, 213-214.

[6] See: Bayly and Harper, Forgotten Armies, 212; Kratoska, Japanese Occupation, 99; Sterling Seagrave, Lords of the Rim: The Invisible Empire of the Overseas Chinese (London: Corgi, 1996), 175-176.

[7] Thio Chan Bee, Extraordinary Adventures of an Ordinary Man (London: Grosvenor Books, 1977), 36.

[8] A report by the news agency Domei on 3 March 1942 cites that those captured were anti-Japanese Chinese and anti-Axis persons; Cheah, Red Star, 22. In the Asahi Shimbun article of 4 March 1942, those captured were referred to as ‘Chinese suspects;’ Chua Ser Koon, “The Japanese’s View of the War 50 Years After.”

[9] Qiu Jing Fu, ed. Rizhishiqi Senzhou Huazu Mengnan Shiliao [A Historical Record of the Suffering of the Negeri Sembilan Chinese People under the Japanese Occupation] (Seremban: Negeri Sembilan Chinese Assembly Hall, 1988).

[10] Akashi, “Japanese Policy,” 63.

[11] Watanabe Wataru, Daitoa Senso Kaisoroku, Part 1: Syonanhen, 437-438; quoted in Akashi, “Colonel Watanabe Wataru,” 40.

[12] Morrison, Malayan Postcript, 171-172. Morrison’s observations aside, it should be noted that there were displays of bravery by non-Chinese in the defence of Singapore. For example, Malay officers Lt. Adnan Saidi, Captain Yazid Ahmad and Warrant Officer Ismail’s heroics have been recognised; see Abu, “Impact of the Japanese Occupation,” 10-11; and Blackburn and Hack, War Memory, 212-216.

[13] Cheah, Red Star, 19; Kratoska, Japanese Occupation, 40; Ban Kah Choon and Yap Hong Kuan, Rehearsal for War: The Underground War Against the Japanese (Singapore: Horizon Books, 2002), 39.

[14] Hayashi , “Massacre of Chinese,” 236-239.

[15] Masanobu’s role in the sook ching operations remains a source of dispute. See: Hayashi, “Massacre of Chinese,” 237-239; Mamoru Shinozaki, Syonan – My Story: The Japanese Occupation of Singapore (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish, 2006), 28; Ian Ward, The Killer They Called A God (Singapore: Media Masters, 2003); Ban and Yap, Rehearsal for War, 38-39.

[16] F. Spencer Chapman, “Travels in Japanese-Occupied Malaya,” The Geographical Journal 110, 1/3 (1947): 28.

[17] Kratoska, Japanese Occupation, 120.

[18] Akashi, “Japanese Policy,” 89.

[19] Cheah, Red Star, 41.

[20] Akashi Yoji, “An Annotated Bibliographical Study of the Japanese Occupation of Malaya/Singapore, 1941-45,” 259.

Among the Malayan population, the Chinese population in particular was regarded as suspect and treated as such. During the cleansing operations, Chinese civilians – primarily men aged 18 to 50, though in many cases women, children and the elderly as well – were ordered to assemble at various public spaces, temporary screening centres or detention camps, sometimes for hours or days, without food and water. Some thought they were meant to register for work or ‘safe’ passes. In other cases, a ruse was used to encourage compliance. In Taiping, the town’s inhabitants were told to gather to receive favourable news.[4] They were then screened. Those who ‘passed’ were released, those who ‘failed’ were taken away; many were summarily executed, others disappeared. Similar scenes were played out across the territory: at a screening centre in Johor Bahru, one in five were taken away to dig their own graves at the Civil Service Club, others were machine-gunned along the seafront; in Malacca, around 90 members of the Straits Settlement Volunteer Forces (SSVF), including five Malay officers, were assembled along three trenches and shot; in Singapore, those killed at Changi Beach were so numerous that it took almost three weeks to bury their bodies.[5]

A typical screening scene involved filing past a Japanese officer, and beside him, a hooded or masked informer or sometimes a known Japanese resident.[6] The identities of the informers remain open to speculation. Some believed them to be renegade Taiwanese or Japanese agents, captured triad members, or simply individuals seeking revenge for past wrongdoings or favours with the new administration. At times, questions were asked about language, schooling and residence. Other times, the assembled were sorted en masse, by a show of hands or by category: civil servants, students, petty hawkers, and so on. In some cases, no words were exchanged, a cursory glance was all that was required; those with tattoos were thought to be triad members, while those from the Hainanese dialect subgroup were assumed to be communists. The educated – civil servants, lawyers and teachers – were also considered threats. Wearing spectacles was taken to be indicative of intellectual status. Thio Chan Bee recounted how he narrowly escaped by ignoring the order to assemble at the Jalan Besar camp in Singapore. There, two of his less fortunate but equally bespectacled colleagues were never seen again.[7]

The number of victims killed during this period has not been ascertained. In Singapore alone, 70,699 were captured; the number of survivors is unknown. Japanese propaganda justified these actions as a preemptive strike against anti-Japanese and criminal elements.[8] Details of massacres on the Malayan peninsula during this time are fragmented. It appears that villages, towns and cities with large Chinese populations were particularly affected. In some cases, the inhabitants of entire villages, such as those in Simpa, Parit Tinggi, Jelulung and Johol, were massacred.[9] In these locations, screening operations were dispensed with; men, women and children were simply rounded up and killed.

Scholars have since debated the severity and causes of the sook ching massacres. In his analysis of the Malai Gunsei or Japanese military administration in Malaya, Japanese historian Akashi Yoji concludes that, despite initial proposals to solicit Chinese cooperation, “the voice of moderation fell by the wayside.”[10] He fingers Watanabe Wataru, the deputy chief of the gunsei, as the primary voice of excess. According to Akashi, Watanabe’s previous experience of guerrilla resistance in China convinced him that the “crafty as anything and hard to control” Chinese “should be dealt with unsparingly.”[11]

Other historians have suggested that the last-stand battle for Singapore played its part in precipitating the massacres. During the siege, Japanese forces met with tenacious but ineffective defence on the part of Chinese irregulars of the SSVF. These volunteers had been called upon only two weeks before the Japanese arrival and were barely trained and poorly armed. Despite this, Ian Morrison, the Australian war correspondent for The Times, observed that they “put up a good fight” for “they had what the Indian and Malay troops lacked, personal venom against the Japanese, who for four years had been killing their fellow countrymen in China.” However, rather presciently, Morrison also predicted that this could lead to “terrible reprisals once the Japanese armed forces were in full control.”[12] Several historians, among them Cheah Boon Kheng, Paul H. Kratoska and Yap Hong Kuan, concur with Morrison’s view.[13]

Japanese historian Hayashi Hirofumi however refutes that the massacres were retaliatory, pointing to the lack of corroborative Japanese sources to substantiate this conjecture. He argues instead that the massacres were a progressive escalation of tactics adopted in China, pointing to Yamashita, who led the invasion forces, as “the link that connected Japanese atrocities in Manchuria and North China with those in Singapore.”[14] In his prior posting as Chief of Staff of the North China Army, he had become acquainted with Watanabe, then head of the Tokomu Kikan espionage unit. Hayashi suggests that Yamashita and Watanabe were staunch supporters of genju shobun (harsh disposal) and genchi shobun (disposal on the spot) methods honed in Manchukuo and north China. Yet others have pointed to Masanobu Tsuji, who headed the Doro Nawa research unit and was subsequently operations officer of the invading 25th Army, as the mastermind behind the Chinese massacres.[15]

The massacres triggered a series of unforeseen consequences. Many Chinese fled the cities for the interior, thus depressing trade and industry further. Others became incentivised to join guerrilla groups in the jungles, among them “rubber-tappers, tin-mining coolies, and vegetable gardeners,” not because of ideological motivations but just so they could “‘have a crack at the Jap.”[16] Kratoska has suggested that the intent of the massacres may have been to “bludgeon the entire Chinese population into submission;” however, its effect was to generate “hatred among people who might otherwise have acquiesced to Japanese rule.”[17] In response, the Chinese adopted a “recalcitrant and intransigent attitude” which “inspired still more harsh methods of repression.”[18] Attempts in late 1943 to pacify the Chinese by integrating them into business, education and government advisory councils could not breach these initial hostilities; instead, “the Chinese reciprocated with non-cooperation and resistance.”[19]

In his unpublished memoirs, Major General Fujimura Masuzo, who succeeded Watanabe in 1943, emphasised the perennial Chinese thorn in the side of the Japanese military administration. The Malai Gunsei he opined was in actuality a Kakyo Gunsei or Overseas Chinese administration. Its duties were hindered by the continuous need to deal with the Chinese for “it was the Kakyo who organised an anti-Japanese army, the Kakyo who cooperated with the gunsei, and the Kakyo who opposed cooperation with the gunsei.”[20] Just like the British before them, the Japanese had to contend with the shifting sands of factionalised Chinese allegiances.

Additional Notes

The prominence of the sook ching massacres in historical discourse has inadvertently promoted several misperceptions. The first concerns the extent of the shukusei or cleansing operations. Thus far, academic attention has been predominantly focussed on events in Singapore. This is not necessarily the result of scholarly neglect. Shukusei was initiated in Singapore before ‘mopping up’ operations moved up the peninsula. It was in Singapore that the magnitude of its effects was most felt, owing to the size of the Chinese population relative to other ethnic groups, and in full view of witnesses, which produced multiple corroborating accounts. Further, these killings achieved a measure of sensationalism during the Singapore Chinese Massacres Trial after the war.

In contrast, shukusei operations on the peninsula have become peripheral to the main event in Singapore. It is only belatedly that historians have linked other mass killings on the peninsula to the sook ching. [See for example: Geoffrey C. Gunn’s article “Remembering the Southeast Asian Chinese Massacres of 1941-45” in Journal of Contemporary Asia 37, 3 (2007): 273–291]. As a result, the first known massacre in Pasir Puteh on 20 December 1941, shortly after the initial Japanese landings off the coast of Kelantan, has been recognised as a “prelude or testing ground” for the purge which came after. There, Chinese male inhabitants were asked to assemble after which five were executed for refusing to hand over the local branch’s China Relief Fund ledgers. Accounts of massacres in other locations from February to April 1942, such as those which occurred in Penang, Kuala Lumpur, Negeri Sembilan and Johor have been documented, though they too have received less detailed attention. Consequently, knowledge of shukusei operations on the peninsula is piece-meal; they do not evoke a similar spectre to the sook ching massacres in Singapore.

Further, disproportionate attention to the sook ching massacres appears to imply that other atrocities were neither significant nor prevalent. Archival research of the war crimes trials refutes this perspective. In terms of geographical distribution, atrocities were documented throughout the Malay Peninsula, Singapore and British Borneo. The scenes were varied, from remote villages to larger towns and cities. The alleged crimes span the duration of the occupation, from February 1942 to September 1945, with little temporal reprieve from violence. The final months were particularly intense amid concerted efforts to eliminate blacklisted persons, potential witnesses and suspected political agitators. Atrocities persisted in the interim between the Japanese surrender on 15 August 1945 and British reoccupation several weeks later.

[1] Masanobu, Japan’s Greatest Victory, xvi. For a more recent analysis of Japanese military strategy in this campaign, see: David J. Mollahan, et. al., The Japanese Campaign in Malaya: December 1941-February 1942, A Study in Joint Warfighting (Norfolk: Joint Forces Staff College, 2002).

[2] It should be noted that Yamashita denied knowledge of the purge conducted in Singapore. He blamed the commander of the Kempeitai but could not remember the name of the officer. See: Report on Interrogation of General Tomoyuki Yamashita by Major C.H.D. Wild, “E” Group, SEAC at Manila, 28 October 1945, WO325/30, TNA.

[3] Bayly and Harper, Forgotten Armies, 211.

[4] Cheong Peng Yeap, “Sejauh Manakah Pendudukan Jepun di Taiping Mempengaruhi Kehidupan Seharian Komuniti Cina di Sana?” [To What Extent Did the Japanese Occupation Affect the Daily Life of the Chinese Population in Taiping?] (Essay, Penang: Universiti Sains Malaysia); quoted in Kratoska, Japanese Occupation, 99.

[5] Bayly and Harper, Forgotten Armies, 213-214.

[6] See: Bayly and Harper, Forgotten Armies, 212; Kratoska, Japanese Occupation, 99; Sterling Seagrave, Lords of the Rim: The Invisible Empire of the Overseas Chinese (London: Corgi, 1996), 175-176.

[7] Thio Chan Bee, Extraordinary Adventures of an Ordinary Man (London: Grosvenor Books, 1977), 36.

[8] A report by the news agency Domei on 3 March 1942 cites that those captured were anti-Japanese Chinese and anti-Axis persons; Cheah, Red Star, 22. In the Asahi Shimbun article of 4 March 1942, those captured were referred to as ‘Chinese suspects;’ Chua Ser Koon, “The Japanese’s View of the War 50 Years After.”

[9] Qiu Jing Fu, ed. Rizhishiqi Senzhou Huazu Mengnan Shiliao [A Historical Record of the Suffering of the Negeri Sembilan Chinese People under the Japanese Occupation] (Seremban: Negeri Sembilan Chinese Assembly Hall, 1988).

[10] Akashi, “Japanese Policy,” 63.

[11] Watanabe Wataru, Daitoa Senso Kaisoroku, Part 1: Syonanhen, 437-438; quoted in Akashi, “Colonel Watanabe Wataru,” 40.

[12] Morrison, Malayan Postcript, 171-172. Morrison’s observations aside, it should be noted that there were displays of bravery by non-Chinese in the defence of Singapore. For example, Malay officers Lt. Adnan Saidi, Captain Yazid Ahmad and Warrant Officer Ismail’s heroics have been recognised; see Abu, “Impact of the Japanese Occupation,” 10-11; and Blackburn and Hack, War Memory, 212-216.

[13] Cheah, Red Star, 19; Kratoska, Japanese Occupation, 40; Ban Kah Choon and Yap Hong Kuan, Rehearsal for War: The Underground War Against the Japanese (Singapore: Horizon Books, 2002), 39.

[14] Hayashi , “Massacre of Chinese,” 236-239.

[15] Masanobu’s role in the sook ching operations remains a source of dispute. See: Hayashi, “Massacre of Chinese,” 237-239; Mamoru Shinozaki, Syonan – My Story: The Japanese Occupation of Singapore (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish, 2006), 28; Ian Ward, The Killer They Called A God (Singapore: Media Masters, 2003); Ban and Yap, Rehearsal for War, 38-39.

[16] F. Spencer Chapman, “Travels in Japanese-Occupied Malaya,” The Geographical Journal 110, 1/3 (1947): 28.

[17] Kratoska, Japanese Occupation, 120.

[18] Akashi, “Japanese Policy,” 89.

[19] Cheah, Red Star, 41.

[20] Akashi Yoji, “An Annotated Bibliographical Study of the Japanese Occupation of Malaya/Singapore, 1941-45,” 259.